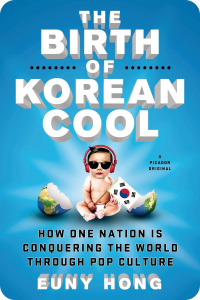

Euny Hong offers a jaunty, fond, and acidic look at South Korea in The Birth of Korean Cool. It’s an unusual and occasionally uneven mix of memoir and ethnography, but the writer’s honesty and irreverence made me even more curious about a place both transparent and labyrinthine.

Hong includes an overview of the Tess of the D'Urbervilles-esque epic known as the story of the Korean peninsula, which has endured over 400 invasions throughout its history while never being the sole invader of another country. Many of these incursions were the work of the Japanese, who last occupied it from 1910 to 1945, and whose domineering fingerprints still haunt South Korea’s self-esteem. To wit, the two countries became the first and last co-hosts allowed by FIFA following a tetchy 2002 World Cup, fight over the naming of the Sea of Japan, and otherwise engage in exacting revenge for put-downs both real and imagined.

This background is closely linked to the concept of han, which loosely translates as a sorrow or injustice so profound that the universe can never hope to compensate for it. This, in turn, leads to a certain sensibility—one that includes frequent roadside fisticuffs, instant and permanent shunning, and a beloved folk song that wishes gangrene upon its object of affection. It’s also been credited with the meteoric economic rise that powered South Korea’s GDP, which was less than Ghana's in 1965, to the fifteenth-largest in the world.

Hong, who grew up in suburban Chicago and the Gangnam area of Seoul, offers up a series of compelling tidbits throughout the book. Beginning in the tenth century, all males except those in the very lowest stratum of society could elevate their entire families into the aristocracy by passing the kwako, a notoriously grueling exam. Titles and privileges remained unless three male heirs in a row failed the test, which would send the family tumbling to whence it came. Another one: the South Korean government is currently wiring every single household with a one gigabit-per-second internet connection, which is 200 times faster than the average American connection. And another: the South Korean government funds 25 percent of its startups. It's a scattershot approach, but it worked for me.

South Korea is also, as the title suggests, an aggressive player in the lucrative pop culture market. During the 1997 IMF loan crisis, they endured the so-called Day of Humiliation, which saw the issuing of a $57 billion loan—of which only $19 billion was used—that was fully repaid by 2001. After that, South Korea got serious about diversifying its portfolio, which consisted of a dozen huge companies vulnerable to market fluctuations. So they added pop music, movies, and television shows into their mix, and nurtured these talents with a $1 billion investment fund. The idea was to create a readily digestible pop culture arsenal that will be easy to sell in emerging economies and will seamlessly integrate with South Korean tech toys. And these countries will be predisposed to like it since they will also be the beneficiaries of South Korean wealth kits, which include funding, an army of nation-building experts, and web of strategic partnerships.

South Korea is aiming to make the twenty-first century its own. It was, quite frankly, terrifically exciting to read about a country so focused, efficient, and savvy while we await another debt ceiling crisis amid a crumbling infrastructure and the relative trickle of our overpriced internet speeds.